by Michelle Graessle

The barely full tour bus hit every bump in the unfamiliar road with little regard to its travel-worn passengers as it made its way toward the city. This particular bus was not immune to typical characteristics of other buses. The smell was stale and the air slightly stagnant. Seemingly unsuspectingly, this bus rolled along the highway in typical fashion; however, it was only a matter of time before this bus and its cargo would be enveloped by a foreign culture steeped in such a colorful history and taken completely by surprise.

The best way to describe a driving tour of Germany’s capital city Berlin is as a virtual reality history book. Instead of reading from a text, Liane Schulz, our tour guide is talking about what happened over a worn-out PA system. Instead of looking at pictures, the Point Park passengers are seeing it with their own eyes.

“And if you’ll look to your left, you’ll see the Brandenburg Gate,” she nonchalantly mentions.

The Brandenburg Gate has had an interesting view on so many decades of history, its symbolism changing with the times. Originally upon its inception, it was a symbol of peace. Then in Nazi times, it was a symbol of the party. It had a front row seat to that long, terrible reign and then later the end of the Berlin Wall.

As the bus rolled on, the tour guide mentioned another interesting tidbit about Berlin. “We have 170 museums in Berlin. That’s more museums than days it’s raining here,” Schulz said.

And how couldn’t there be? With so much history to explore, it comes as no surprise that Berlin is home to a multitude of museums. The tour guide pointed out a museum at Checkpoint Charlie, one of the former connecting points between East and West Berlin. There is the Topography of Terrors that chronicles many aspects of Germany under Nazi rule, which was very close to the group’s hotel in Berlin, and there are also many diverse art museums to visit, many on Museum.

Just as diverse, Schulz explains, are the types of people living in Berlin. Of the 3.5 million citizens, the top three groups of immigrants come from Turkey, Croatia and other parts of Eastern Europe. One hundred and eighty countries are represented in this 775-year-old melting pot of a city. Also included in the population of Berlin are students. Berlin is the setting for to four universities and around 260,000 students. Because of this, nightlife is a large part of Berlin’s culture, giving it a unique reputation to the rest of Germany.

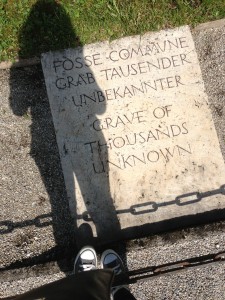

Berlin attracts 1.2 million visitors per year, the guide said. Also not a surprise as on a driving tour alone the students saw the Reichstag building, Potsdamer Platz and the Sony Center, the Victory column, also known by American soldiers in World War II as the “Chick on a Stick,” and so many other iconic tourist destinations and historically relevant locations. The Point Park students and faculty stretched their legs at the Holocaust Memorial, a striking outdoor sculpture and commemorative museum in the midst of their initial tour.

This dynamic and diverse city also offers other unique experiences to travelers in its distinctive gastronomy and cultural nuances. If a tour bus could talk, it would tell visitors that Berlin is a must see for anyone interested in Germany as a travel destination.